JIM MCMAHON/MAPMAN ®

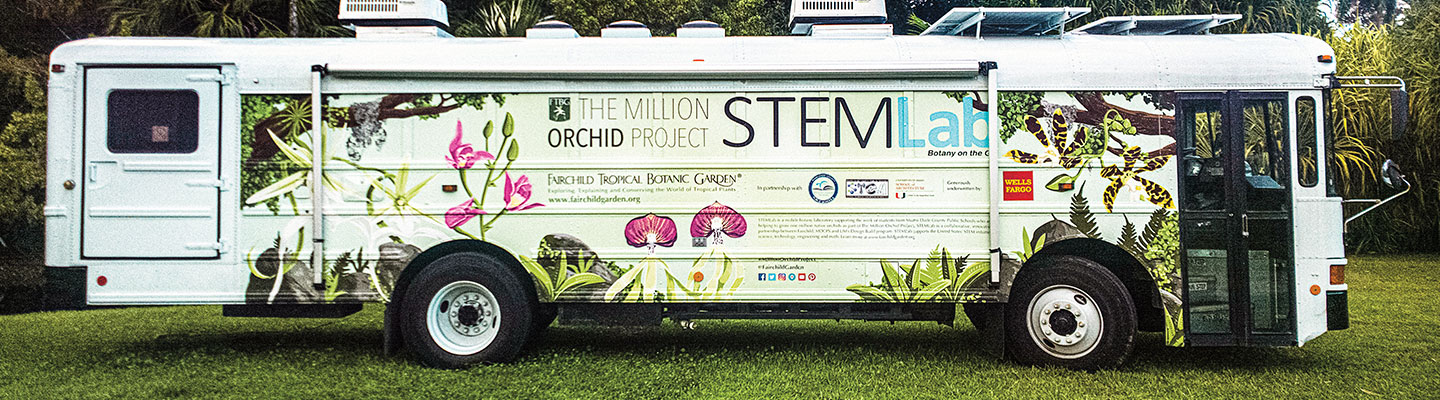

Every Friday during her sophomore year, Alexa Martinez would leave BioTech High School in Miami, Florida, and hop on a bus parked outside. It wasn’t a typical yellow bus used to transport kids to and from school, though—it was a botany lab on wheels. The vehicle, called the STEMLab, was created as part of the Million Orchid Project to give students like Alexa the chance to study and protect local plants.

The project, launched by the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, aims to plant 1 million orchids in urban areas across South Florida. The garden’s botanists hope the effort will save the state’s six native orchid species from extinction in the wild. BioTech is one of 100 local schools that have partnered with the botanical garden to help out. Students at member schools get to work in the STEMLab and learn all about how flowering plants reproduce and grow (see From Seed to Plant).

Alexa Martinez left BioTech High School in Miami, Florida, and hopped on a bus outside. She did this every Friday during her sophomore year. But it wasn’t a normal yellow bus that took kids to and from school. It was a botany lab on wheels. The vehicle is called the STEMLab. It’s part of the Million Orchid Project. The lab was created to give students like Alexa the chance to study and protect local plants.

The project aims to plant 1 million orchids in urban areas across South Florida. It was started by the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden. Florida has six native orchid species, and the garden’s botanists hope to save them from disappearing in the wild. To help out, 100 local schools have teamed up with the botanical garden. BioTech is one of them. Students at member schools get to work in the STEMLab. They learn all about how flowering plants reproduce and grow (see From Seed to Plant).

Students sterilize glass milk bottles to remove any microbes and fill them with a nutrient-rich jelly called agar. They sprinkle dust-size orchid seeds into each bottle.

Students sterilize glass milk bottles to remove any microbes and fill them with a nutrient-rich jelly called agar. They sprinkle dust-size orchid seeds into each bottle. Students seal the bottles and place them on racks under a sunlamp to help the seeds grow.

Students seal the bottles and place them on racks under a sunlamp to help the seeds grow. The orchids eventually outgrow their first containers. Students replant them into larger ones to continue growing.

The orchids eventually outgrow their first containers. Students replant them into larger ones to continue growing. Once the orchid has matured into a plant that can survive in the wild, students transplant it to a suitable tree. Now it’s up to nature to take over.

Once the orchid has matured into a plant that can survive in the wild, students transplant it to a suitable tree. Now it’s up to nature to take over.