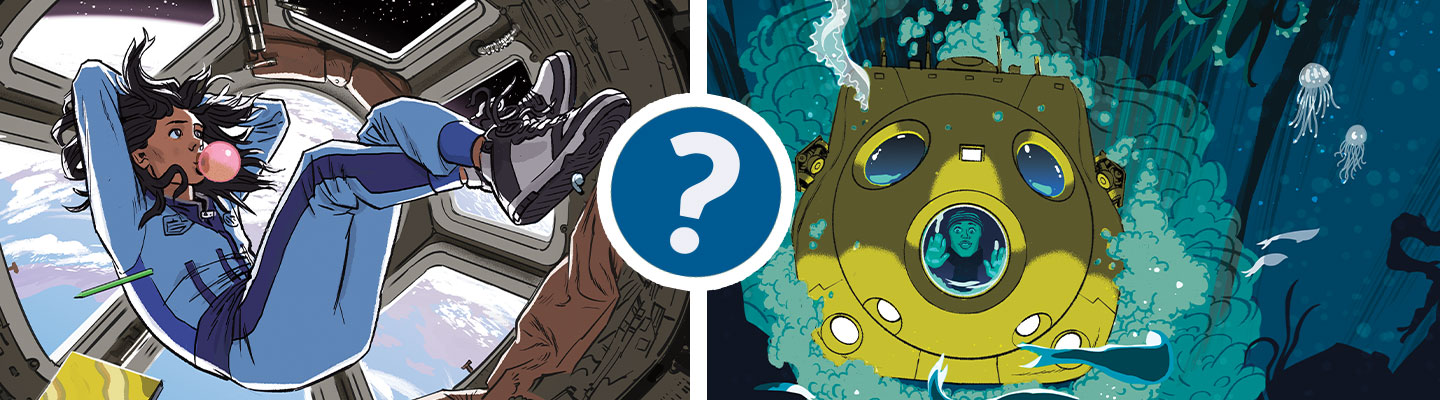

Right now, an enormous laboratory called the International Space Station (ISS) is circling Earth 409 kilometers (254 miles) above the planet’s surface. The station allows a crew of up to seven people to live and work in the airless void of space for months at a time. Spanning the length of a football field, the ISS is made up of connected modules where astronauts can eat, sleep, exercise, and perform experiments.

Right now, a huge laboratory is circling Earth, 409 kilometers (254 miles) above the planet’s surface. It’s the International Space Station (ISS). It holds a crew of up to seven people. For months at a time, the station allows them to live and work in the airless void of space. The ISS is as long as a football field and is made up of connected modules. Astronauts can eat, sleep, exercise, and perform experiments in them.